Inside the fortified rooms securing U.S. secrets

Every year, the federal government classifies tens of millions of documents. To see the most sensitive ones, you need top-level security clearance. And you need a SCIF.

A SCIF (pronounced “skiff”) is a sensitive compartmented information facility. It’s an ultra-secure room where officials and government contractors take extraordinary precautions to review highly classified information.

Their role in safeguarding the nation’s secrets has come under scrutiny following the leak of classified military intelligence on social media this month, and the recent discovery of unsecured classified documents at the homes of former president Donald Trump, former vice president Mike Pence and President Biden, as well as an office Biden used before becoming president.

Federal investigators say Jack Teixeira, the National Guardsman charged in the intelligence leak, had a security clearance that allowed him to access top secret materials, which must be stored and handled in a SCIF in all but the narrowest circumstances. He is accused of posting hundreds of highly classified documents on the messaging platform Discord, where, his online friends told The Washington Post, he bragged about getting to view intelligence in a SCIF on a Massachusetts military base.

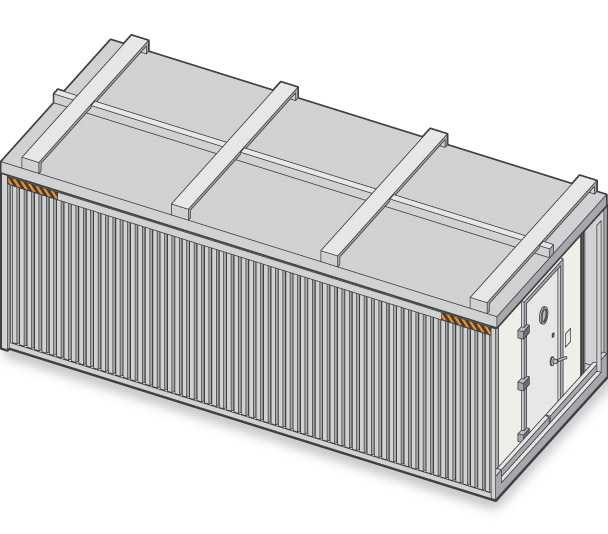

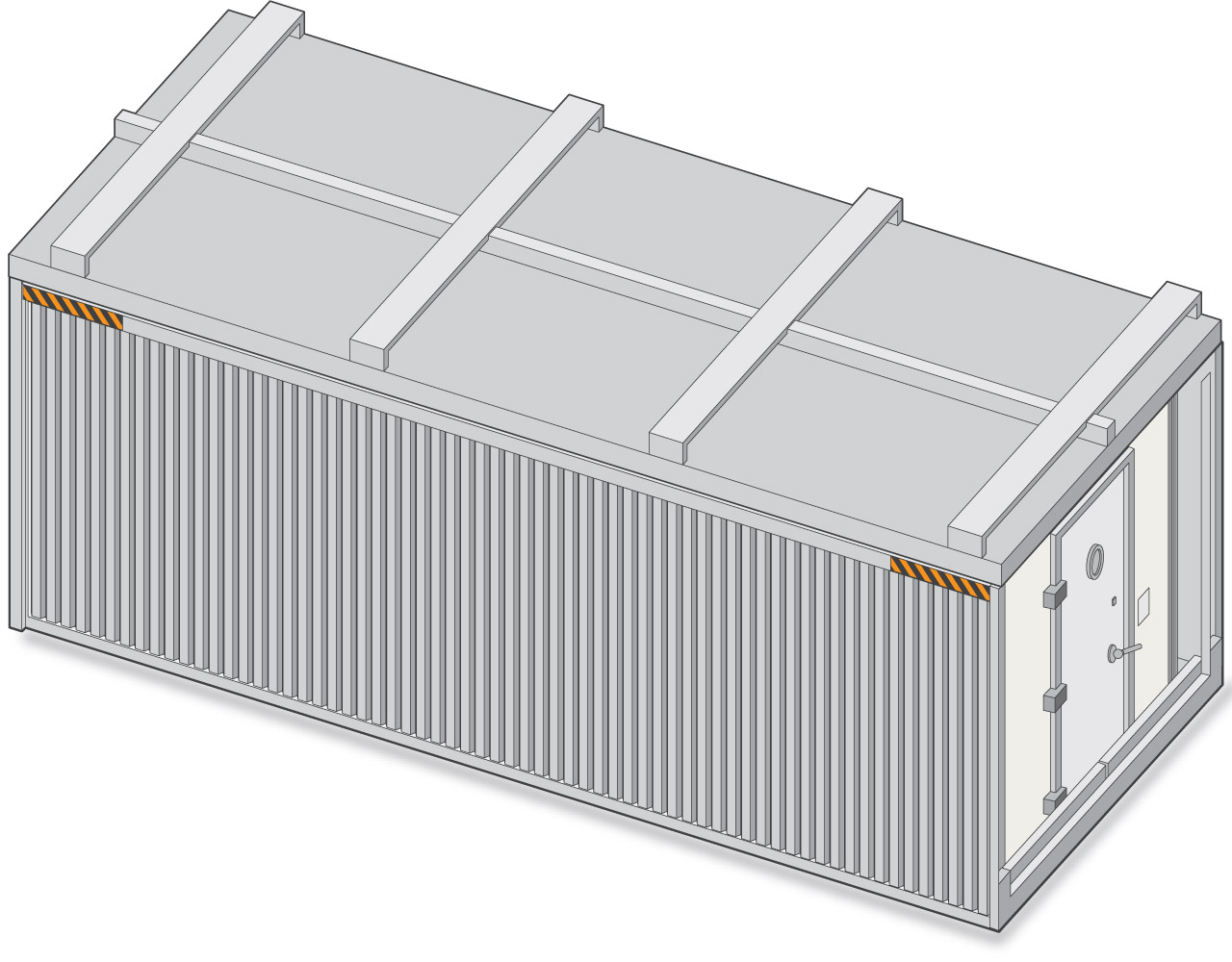

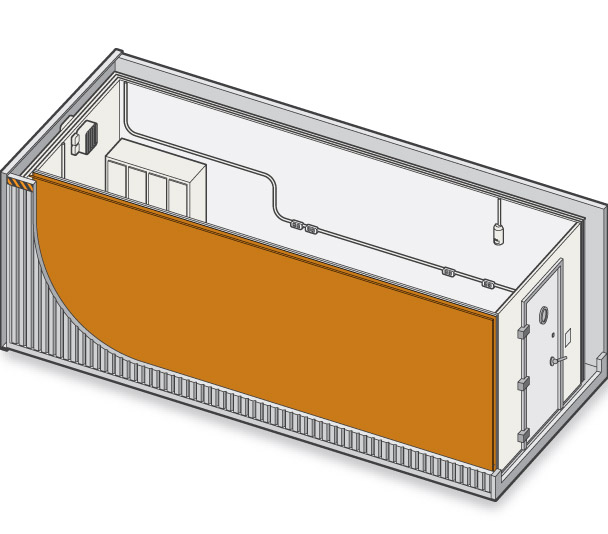

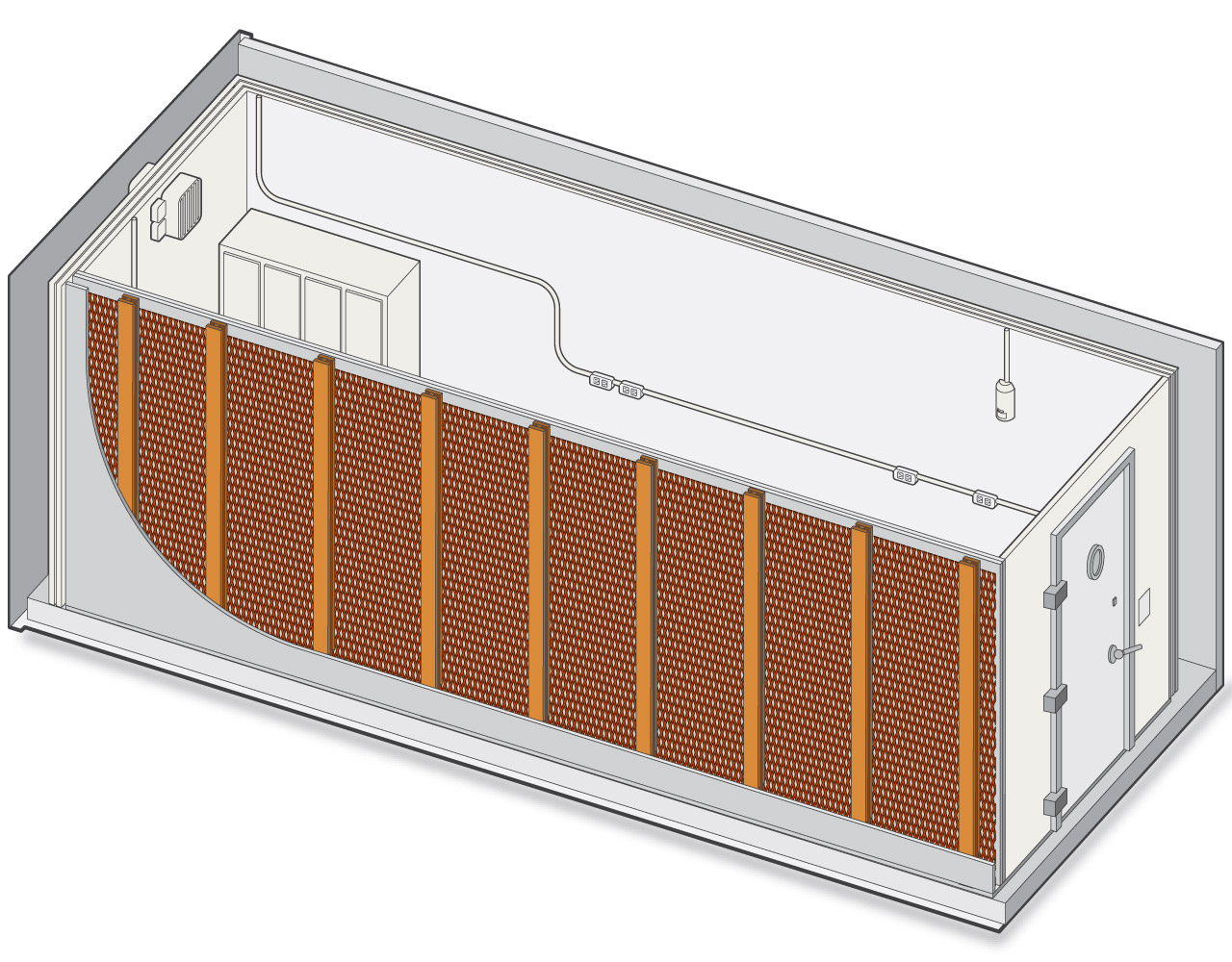

The following SCIF renderings, created by The Post, are based on a review of construction specifications from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, which sets standards for how SCIFs are built, and interviews with SCIF contractors and former national security officials.

There are thousands of SCIFs in Washington and beyond, tucked into federal buildings, military installations, embassies and government contracting offices. They can range from phonebooth-sized rooms to entire floors of buildings.

One common design type, shown here, is a SCIF built into a metal shipping container.

The perimeter walls are layered with gypsum board and plywood, then sheathed in a material that prevents electronic eavesdropping.

Mesh and metal studs are used to further harden the room against forced entry.

Soundproofing material and acoustic sealant are added to prevent anyone from listening in.

Doors are outfitted with special deadbolts, combination locks and access control systems that typically require both badges and personal identification numbers for entry.

Vents and ducts above a certain size are blocked with metal bars, to keep outsiders from sneaking in. “The whole Tom Cruise scene in ‘Mission: Impossible’ — that can’t happen because you can’t get through,” said Phil Chance, president of the SCIF contractor Adamo Security Group.

All of the wiring, outlets and light switches must be wall-mounted. If they’re flush with the wall, like in a typical home or business, “it creates a vulnerable point, and there could more easily be acoustic leaks,” Chance said.

Motion sensors monitor for movement when the SCIF is empty.

In some cases, a guard must be on-site to protect stored documents, or be capable of responding within five minutes.

Despite all of those safeguards, SCIFs often function like normal offices, with workstations and space to hold meetings. But cellphones and other unsecured devices are barred.

“You can always tell a SCIF newbie,” said Emily Harding, a former deputy staff director for the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and a former CIA analyst. “They don’t know what they can bring with them.”

The point of this meticulous construction is what the intelligence community calls “security in depth” — overlapping layers of protection that slow down adversaries and detect intrusions long before a breach actually occurs.

“It is not just ‘close the door’ — it’s ‘lock the door with a sophisticated lock, and shield the walls against any kind of external monitoring,’” said Steven Aftergood, a classified information expert.

Presidents, vice presidents and some high-ranking officials set up SCIFs in their homes, often in garages or extensions that are easy to retrofit.

With a few exceptions, highly classified materials — including top secret documents and information gleaned from intelligence sources — are never supposed to leave a SCIF.

And yet, FBI agents found stacks of them last year in a storage area in Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s home and private club, according to court filings. While it’s not yet publicly known what types of classified documents were found in Biden’s home and pre-presidential office, and in Pence’s home, law enforcement are investigating whether these situations, too, could be significant breaches of national security.

Classified documents and who gets clearance to read them

Many of the millions of documents the federal government classifies each year receive a low-level classification. In theory, they could compromise national security if exposed. But as a practical matter, they probably won’t, said Bruce Riedel, a former longtime CIA official and National Security Council staff member.

Top secret information includes weapon designs and war plans.

The exposure of these materials could cause “exceptionally grave damage” to national security.

Information marked top secret or SCI must remain in a SCIF or in the custody of a cleared CIA or National Security Council official.

TOP SECRET/SCI

THIS IS A COVER SHEET

FOR CLASSIFED INFORMATION

TOP SECRET/SCI

Secret information includes a report from a U.S. Embassy overseas.

Its exposure could cause "serious damage" to national security.

Information marked secret can be kept in a government office such as the Pentagon or the State Department, provided it is properly locked up when the office is empty.

SECRET

THIS IS A COVER SHEET

FOR CLASSIFED INFORMATION

SECRET

Confidential information may include basic State Department cables.

It could “damage” national security.

Information with this this low-level classification doesn't need to be stored or reviewed in a SCIF.

CONFIDENTIAL

THIS IS A COVER SHEET

FOR CLASSIFED INFORMATION

CONFIDENTIAL

CONFIDENTIAL

SECRET

TOP SECRET/SCI

THIS IS A COVER SHEET

FOR CLASSIFED INFORMATION

THIS IS A COVER SHEET

FOR CLASSIFED INFORMATION

THIS IS A COVER SHEET

FOR CLASSIFED INFORMATION

CONFIDENTIAL

SECRET

TOP SECRET/SCI

Type of

information

It may include basic State Department cables.

Secret includes a report from a U.S. Embassy overseas

Top secret information includes weapon designs and war plans.

Risk level

It could “damage” national security.

Its exposure could cause “serious damage” to national security.

The exposure of these materials could cause “exceptionally grave damage” to national security.

SCIF

required?

NO

Information with this this low-level classification doesn't need to be stored or reviewed in a SCIF.

NO

Information marked secret can be kept in a government office such as the Pentagon or the State Department, provided it is properly locked up when the office is empty.

YES

Information marked Top Secret or SCI must remain in a SCIF or in the custody of a cleared CIA or National Security Council official.

“If you’re the vice president and you’re going to Poland, there will be all kinds of traffic between the White House and the embassy saying, ‘He’s arriving on this flight, his staff is arriving on this flight.’ All that is going to be classified,” Riedel said. “As soon as the trip happens, that’s all public, but the document remains stamped ‘confidential.’”

Riedel said he wouldn’t be surprised if some of the documents found at Biden’s home and office and in Pence’s house fell into that low-level category. “Yes, technically the document hasn’t been appropriately cared for,” he said, “but nobody is going to say, ‘This is a national security threat.’”

In Trump’s case, some of the documents FBI agents seized were clearly marked “top secret/SCI,” meaning they contained information gleaned from secret intelligence sources and methods. At least one document described Iran’s missile program; other papers described sensitive intelligence work involving China.

“That kind of material should never be outside a SCIF,” Riedel said.

The Discord leaks also involved many documents with top-tier classification. They included battlefield assessments of the war in Ukraine, information about U.S. infiltration of the Russian military, and details about China’s spy balloons.

Federal investigators say Teixeira, a 21-year-old technology staffer with the Massachusetts Air National Guard, initially transcribed classified documents and posted the text in a small, invite-only Discord chatroom. Later, he started bringing documents home, taking pictures of them and sharing those images, investigators allege. Other users shared the documents outside the group, and the material soon migrated to the wider internet for the world to see.

Investigators have not yet said how they believe Teixeira was able to remove the materials from his workplace.

But the case appears to highlight critical weaknesses in the way the U.S. government manages its secrets, according to intelligence and national security experts.

Teixeira is among more than 1 million government employees and contractors whose security clearances give them access top secret information, including information about sources and methods used to gather intelligence. More than 1 million others have access to materials with lower classifications.

The government issues those clearances to ensure that there are enough people available to handle and process its huge volumes of classified information. “The military and the intelligence community cannot exist without people — some of them quite junior — being brought into these secrets,” said Robert L. Deitz, former senior councilor to the CIA director and a former general counsel at the National Security Agency.

But allowing so many people to access sensitive materials raises the risk of leaks — both deliberate and accidental.

“Our current system is broken, leaky, and a pernicious threat to our credibility and efficacy,” Tim Roemer, a former ambassador and congressman who served on the 9/11 Commission, said of the Discord leaks. “Too many people have access to too much sensitive information, and too much information is over-classified.”

SCIFs are designed to guard against external threats; without proper oversight, they’re less effective against leaks and blunders that originate inside.

Roemer described the airtight security measures officials took when, as a member of the House, he asked for information about an intelligence operation the United States was engaged in at that time. He couldn’t even take a pen and paper into the SCIF, he said.

“When I was seated, somebody came into the room from the oversight agency from the program. The information they had was handcuffed in a silver briefcase. They had a security person,” he recalled. “I sat down in the room for three or four hours. I could not write anything down. This person sat with me the entire time. As soon as I was done, they sped off back to the government agency, taking the documents with them.”

Officials with high-level security clearances know not to leave classified documents in a trash can or stick papers in their coat pocket. But still, even highly sensitive material can fall victim to human error.

In the Senate, the Intelligence Committee’s SCIF is a room on the second floor of the Hart office building — “a SCIF in the middle of a tourist attraction,” as Harding, the committee’s former deputy staff director, put it. There are days, she said, when a senator may have to run from a classified briefing in the SCIF to an unclassified meeting on health care with constituents in another office.

“As a staffer,” Harding said, “your job is to tackle them if they’re walking out the door and they pick up the wrong folder.”

The rules for handling classified information are different for sitting presidents. They’re free to review top secret materials outside of a SCIF, but even then, they usually do so in the presence of a senior official such as the national security adviser, who is responsible for retrieving the documents and securing them afterward.

In the White House, for example, a briefer from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence typically arrives each morning to deliver the President’s Daily Brief, or PDB, a top secret summary of intelligence from around the world. The president may read it in the Oval Office, but when he’s done, someone from the national security adviser’s office brings it to a SCIF in the West Wing or in the Situation Room for safekeeping.

Presidents also have the authority to declassify documents, though they have used it sparingly. In 2004, then-president George W. Bush declassified part of his daily brief that warned Osama bin Laden was planning to strike the United States. Trump appears to have been more cavalier, tweeting a detailed aerial image of an Iranian launchpad in 2019 that experts said was almost certainly classified.

From the Faraday cage to a billion dollar industry

The idea of a SCIF is nothing new, said Andrew Hammond, the historian and curator at the International Spy Museum. Societies have always wanted to protect their own secrets — and have attempted to steal guarded information from their rivals.

In 1836, scientist Michael Faraday invented the Faraday cage, which is viewed as a precursor to the SCIF. The enclosure blocked electromagnetic fields — one of the technologies used at the time to spy — and government officials would store or read materials in the cage.

Since then, Hammond said protocols to protect American secrets have become more standardized and widespread, with big changes and advancements typically emerging after wars.

A pivotal moment that contributed to the development of the modern-day SCIF, he said, came in 1945, when a group of Soviet children visited the U.S. Embassy in Moscow and gifted the ambassador a hand-carved seal of the United States.

U.S. officials didn’t notice that the seal had a high-tech bug on it that could be activated by a van that would drive by the embassy and emit a radio beam, allowing the people in the van to hear the conversations unfolding inside.

It took seven years to detect the bug. After that, according to Hammond, officials determined they needed protected spaces to discuss secretive national security issues.

“People have always had ways and means to try and protect information,” Hammond said. “But some of those ways and means were not aligned with the most cutting edge technology, so there was an effort to make it professional and more standardized.”

When Mary McCord served as the Justice Department’s acting assistant attorney general for national security, she spent the bulk of her days in an expansive SCIF at the department’s main headquarters. McCord, who has three children, was prohibited from having her cellphone with her, so her husband was typically the point of contact if one of their children’s schools needed to reach them during the day. But one day, she said, her husband was out of the country when her child was injured.

McCord was in a meeting, and the school had to call a legal assistant on the SCIF’s secured landline, who then alerted McCord with a handwritten note.

McCord transported sensitive materials home in a special locked bag. At home, she had a government-installed safe behind a deadbolt. But still, she could only take certain classified documents home — nothing past the secret level — and had to complete some tasks in the more protected SCIF at the Justice Department’s headquarters.

“Sometimes I would have to go in on a weekend because someone would send me something that is classified,” she said. “People had a regular email and an email for classified materials.”

LEFT: President Donald Trump receives a briefing on a military strike on Syria in a secured location at his Mar-a-Lago residence in 2017. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead) RIGHT: President Barack Obama is briefed on the situation in Libya during a secure conference call inside a tent in Brazil in 2011. The tent acted as mobile SCIF, designed to allow officials to have top secret discussions while on the move. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

The government even has strict regulations dictating how sensitive materials must be destroyed, according to Aftergood. Putting documents through a shredder, he said, is insufficient. Classified materials may need to be destroyed if there are duplicates, or if a government facility abroad is under attack.

In 1979, Iran revolutionaries stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking dozens of people hostage. Staffers rushed to shred some of the most sensitive documents in the embassy so that the militant forces could not steal the classified materials.

But it wasn’t enough. The militants pieced the materials back together and published the information, which revealed CIA efforts to recruit Iranian officials and others as agents after the Iranian revolution.

Now, according to Aftergood, certain classified materials need to be burned or pulverized.

“They need to be turned into mush. And electronic records need to be electromagnetically scrubbed before they are scrubbed,” Aftergood said. “It tells you just how seriously the national security agencies take the storage and protection of classified information.”

Photo editing by Thomas Simonetti. Editing by Debbi Wilgoren, Kevin Uhrmacher and Kainaz Amaria. Copy editing by Adrienne Dunn. Additional editing by Courtney Kan.