What’s killing the jump scare?

As Halloween approaches, it’s getting scary out there. But, surprisingly, it’s not as jump-scary as it used to be.

Since 2014, the number of jump scares cranked out by Hollywood has fallen precipitously, according to Where’s The Jump, a remarkable catalog of over 1,000 movies that documents the time stamps of slamming doors, sudden attacks, and other startling moments that can make viewers jump.

This marvelous resource came to our attention because we here at the Department of Data don’t need a creepy movie to startle us out of our skin. Even a loud bird can do the trick. So we appreciate the diligent effort that goes into recording the profusion of shocks in movies like the second “Haunting in Connecticut” film — which, at 32, contains the highest jump count on the site. (Sample scare: At 21:02, “The decomposing corpse appears directly in front of Lisa as she opens her eyes.”)

Then it occurred to us to use this database for a different reason: To track the rise in jump scares from single-jump classics like “Carrie” to more modern, jump-laden films like “Insidious.” We expected to find filmmakers steadily increasing jump scares to crank up tension for jaded viewers. Instead, we found the average number of jump scares per movie decidedly on the decline.

Jump scares reached an early peak in 1981 with the release of movies like “The Evil Dead,” which averaged a jump scare for every four minutes of run time. Another big revival started in the early 2000s and lasted more than 10 years.

But jump scare frequency hit a near-20-year low in 2021. Audiences are still seeing more jump scares than they did in the less-startling 1990s, but the shrieking alley cats, slamming doors and lurking killers of the movie world appear to be fading into the background.

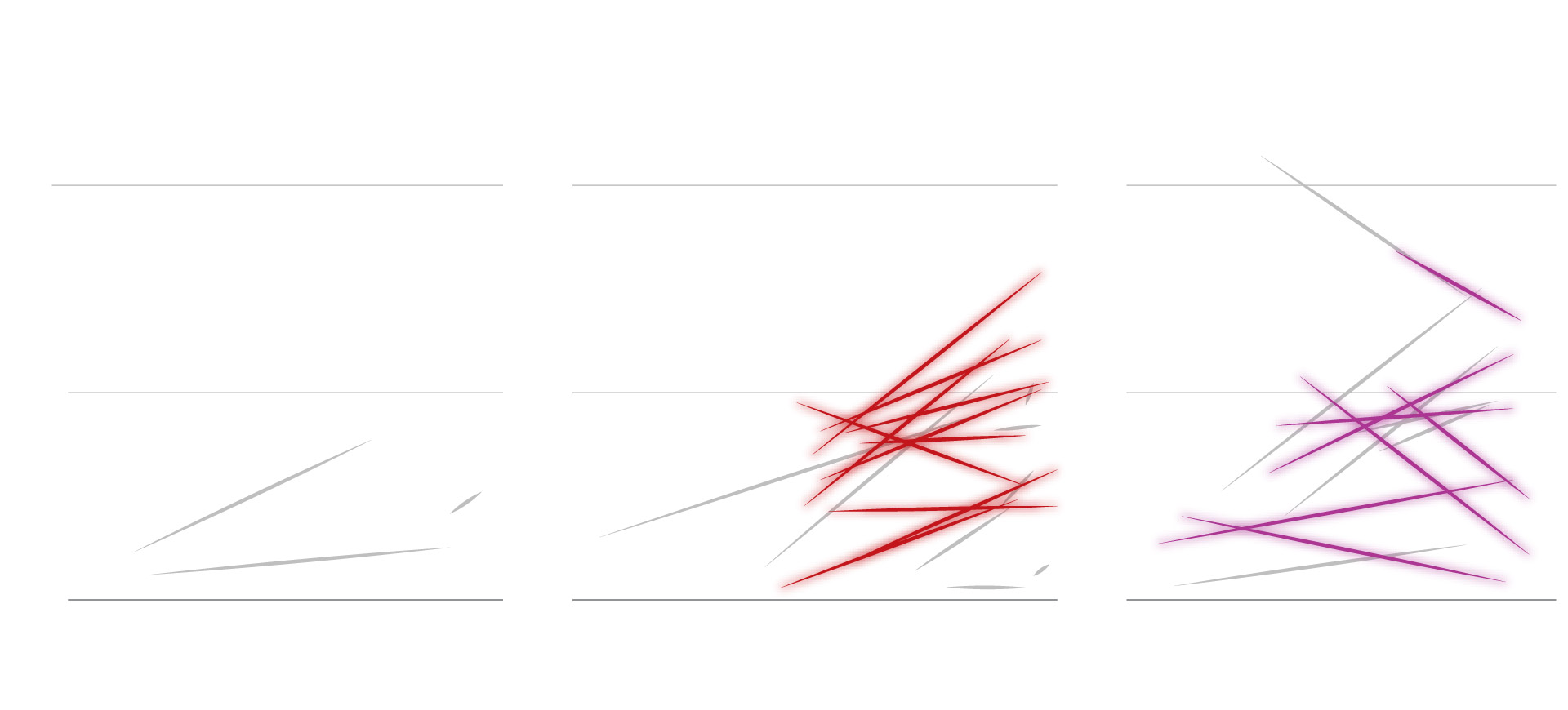

To understand what has changed since 2014, we investigated how jump scares doubled in density between the 1970s and 2014.

The classic horror movies of the 1960s and 1970s, like “Psycho” and “Suspiria,” used jump scares sparingly. Some, like “Rosemary’s Baby,” didn’t feature any jump scares at all. But the slasher franchises of the late 1970s and ’80s introduced a new standard, driving up the overall number of jump scares as killers like Freddy Krueger and Michael Myers mowed their way through hordes of suburban teenagers.

When those slasher franchises rose from the dead as remakes in the 2000s and 2010s, their use of jump scares rose, too, according to Laura Mee, a senior lecturer in film and television studies at the University of Hertfordshire and author of “Reanimated: The Contemporary American Horror Remake.” Remakes, she explained, sometimes pile on jump scares “to do something to move away from the original version, away from their roots, to carve their own identity.”

To see whether remakes typically had more jump scares than their originals — and whether a reduction in remake mania has reduced jump scares since 2014 — we examined 34 instances in which Where’s The Jump contained both the original movie and its remake.

Indeed, 27 of those remakes contained more jump scares than the originals, we found. But that trend has reversed in recent years.

Of the handful of remakes that had substantially fewer jump scares than their original films — just six of 34 — five of them were released in the past 10 years. And every remake released since 2020 has featured a decrease in jump scares. So it’s hard to blame a decline in jump scares on a lack of remakes when jump scares are falling in remakes, too.

The timing of the decrease suggested another suspect. Fellow horror buffs pointed to the rise of what’s known as “elevated” horror beginning in the mid-2010s. Elevated horror, also known as art horror, generally refers to horror films that focus on characterization, social issues and strong visuals rather than guts and spurting blood. Some critics say it’s less a coherent film category than a marketing move to distance movies from horror’s gory past.

Our experts helped us find 19 elevated horror movies in the jump scare data, including “The Witch,” “Get Out,” “Midsommar” and “A Quiet Place.” Those movies tended to have fewer jump scares than other movies released around the same time. However, removing them from the data did not reverse the decrease in jump scares after 2014. That suggests that jump scares also have become less common in your ordinary, run-of-the-mill, non-elevated horror movie.

We started to wonder whether something had changed in the nature of jump scares themselves. Fortunately, Where’s The Jump allows contributors to classify individual jump scares as major (the lawn work tape in 2012’s “Sinister”) or minor (a plethora of shadowy figures and loud noises). Finally, we hit pay dirt: While the number of major jump scares has held steady, minor jump scares have taken a nosedive since 2015.

But the definition of “major” and “minor” is inherently subjective, especially since Where’s The Jump allows its stable of contributors to categorize each jump scare for themselves. So we took another look at the data, this time focusing on the text descriptions of each jump scare to see if we could tease apart some differences.

A little text analysis surfaced four main types of jump scares: Startling sounds. Sudden movements. Unexpected attacks. And reveals of hidden characters. Minor jump scares were more likely to involve sounds than major jump scares, while major jump scares were more likely to include reveals of hidden characters and sudden movements. Major jump scares also were more likely to fall into more than one category.

Minor jump scare

A door suddenly slams or a cat bursts from a trash can. These scares tend to rely on manipulating the viewers’ senses rather than revealing major information that pushes the plot forward.

Major jump scare

A zombie bursts from the ground, revealing that the undead have begun to rise. These scares are more likely to reveal hidden characters and play into expectations about the movie’s narrative.

On closer inspection, however, descriptions of major and minor jump scares tended to look pretty similar, even within the same movie. In 1980’s “Friday the 13th,” for example, Pamela grabbing Jack is listed as a minor scare, while Jason grabbing Alice on the lake is a major scare.

According to Mee, the difference is in the setup. The lake scene is high on her list of favorites because it plays with the audience’s expectations: We think Alice is safe because she’s defeated the movie’s main villain, Pamela. When Jason lunges out of the lake, he shatters that illusion of safety. It’s also frightening because it happens in the final scenes of the movie, a tactic introduced in the 1976 Stephen King classic, “Carrie.”

Chris Catt, an editor at online horror magazine Creepy Catalog, said minor jump scares might be in decline because audiences are increasingly disenchanted with sensory-based scares that don’t tie into a movie’s themes or push the plot forward.

“If you’ve seen a handful of horror movies, you know the basic setups for pretty much every jump scare that’s ever been done,” Catt said. “Filmmakers have to work a lot harder to make a jump scare effective in the modern era.”

Directors are rising to the challenge: Catt and Mee both ranked a scene from the 2018 Netflix show “Haunting of Hill House” among the most frightening they’ve ever seen. But other directors including Jordan Peele, Ari Aster and Robert Eggers have adopted a more restrained approach, rejecting distracting jump scares to focus on filmmaking that ratchets up tension and delivers more disturbing scares that linger.

Mirror jump scare

A character looks in a mirror, then bends down or shifts the mirror’s angle. On next glance, a monster or villain is standing right behind them.

That may be a good strategy, since some classic horror movie tropes have been overused to the point of self-parody. The mirror jump scare is a recent casualty. The word “mirror” appears in more than 100 scenes in the Where’s The Jump database, but its use has declined sharply since the 2010s. Cat jump scares, featuring felines yowling or hiding in a cabinet, peaked in the early 1970s and have since dwindled to nearly nothing.

Cat jump scare

A trash can rattles. A scratch at the window. A shadow moving at the edge of sight. Could it be a monster? The bad guy? MROWR. Just kidding: It’s a cat.

While some jump scares fall out of fashion, even minor jump scares play an important role in horror movies, Mee said. They can help establish a narrative rhythm, release tension or even set up a larger scare by establishing a false sense of security.

“Horror is very visceral and also very subjective,” Mee said. “Jump scares might be the lowest form of fright for numerous audiences. But, equally, some people really love them. Some people just want to be made to jump out of their skin.”

Ahoy, friends! At the Department of Data, fun facts are serious business. See anything we should investigate further? Maybe there are other holiday-oriented film tropes you want us to measure, like the prevalence of small-town vs. big-city tensions in Hallmark Christmas movies. Just ask!

If you follow the column here, we’ll send the answer to each question to your inbox as soon as it publishes. And if we use your idea in a column, we’ll send you a button and a membership card identifying you as an official agent of the Department of Data.