In 2019, when NSO Group was facing intense scrutiny, new investors in the Israeli surveillance company were on a PR offensive to reassure human rights groups.

In an exchange of public letters in 2019, they told Amnesty International and other activists that they would do “whatever is necessary” to ensure NSO’s weapons-grade software would only be used to fight crime and terrorism.

But the claim, it now appears, was hollow.

Unknown to the activists, NSO would later hatch a deal that would help a longtime government client with an awful human rights record. Dubai, a monarchy in the United Arab Emirates, wanted NSO to give it permission to expand its potential use of the spyware so it could target mobile phones in the UK.

Quick GuideWhat is in the Pegasus project data?

Show

What is in the data leak?

The data leak is a list of more than 50,000 phone numbers that, since 2016, are believed to have been selected as those of people of interest by government clients of NSO Group, which sells surveillance software. The data also contains the time and date that numbers were selected, or entered on to a system. Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based nonprofit journalism organisation, and Amnesty International initially had access to the list and shared access with 16 media organisations including the Guardian. More than 80 journalists have worked together over several months as part of the Pegasus project. Amnesty’s Security Lab, a technical partner on the project, did the forensic analyses.

What does the leak indicate?

The consortium believes the data indicates the potential targets NSO’s government clients identified in advance of possible surveillance. While the data is an indication of intent, the presence of a number in the data does not reveal whether there was an attempt to infect the phone with spyware such as Pegasus, the company’s signature surveillance tool, or whether any attempt succeeded. The presence in the data of a very small number of landlines and US numbers, which NSO says are “technically impossible” to access with its tools, reveals some targets were selected by NSO clients even though they could not be infected with Pegasus. However, forensic examinations of a small sample of mobile phones with numbers on the list found tight correlations between the time and date of a number in the data and the start of Pegasus activity – in some cases as little as a few seconds.

What did forensic analysis reveal?

Amnesty examined 67 smartphones where attacks were suspected. Of those, 23 were successfully infected and 14 showed signs of attempted penetration. For the remaining 30, the tests were inconclusive, in several cases because the handsets had been replaced. Fifteen of the phones were Android devices, none of which showed evidence of successful infection. However, unlike iPhones, phones that use Android do not log the kinds of information required for Amnesty’s detective work. Three Android phones showed signs of targeting, such as Pegasus-linked SMS messages.

Amnesty shared “backup copies” of four iPhones with Citizen Lab, a research group at the University of Toronto that specialises in studying Pegasus, which confirmed that they showed signs of Pegasus infection. Citizen Lab also conducted a peer review of Amnesty’s forensic methods, and found them to be sound.

Which NSO clients were selecting numbers?

While the data is organised into clusters, indicative of individual NSO clients, it does not say which NSO client was responsible for selecting any given number. NSO claims to sell its tools to 60 clients in 40 countries, but refuses to identify them. By closely examining the pattern of targeting by individual clients in the leaked data, media partners were able to identify 10 governments believed to be responsible for selecting the targets: Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Morocco, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Hungary, India, and the United Arab Emirates. Citizen Lab has also found evidence of all 10 being clients of NSO.

What does NSO Group say?

You can read NSO Group’s full statement here. The company has always said it does not have access to the data of its customers’ targets. Through its lawyers, NSO said the consortium had made “incorrect assumptions” about which clients use the company’s technology. It said the 50,000 number was “exaggerated” and that the list could not be a list of numbers “targeted by governments using Pegasus”. The lawyers said NSO had reason to believe the list accessed by the consortium “is not a list of numbers targeted by governments using Pegasus, but instead, may be part of a larger list of numbers that might have been used by NSO Group customers for other purposes”. They said it was a list of numbers that anyone could search on an open source system. After further questions, the lawyers said the consortium was basing its findings “on misleading interpretation of leaked data from accessible and overt basic information, such as HLR Lookup services, which have no bearing on the list of the customers' targets of Pegasus or any other NSO products ... we still do not see any correlation of these lists to anything related to use of NSO Group technologies”. Following publication, they explained that they considered a "target" to be a phone that was the subject of a successful or attempted (but failed) infection by Pegasus, and reiterated that the list of 50,000 phones was too large for it to represent "targets" of Pegasus. They said that the fact that a number appeared on the list was in no way indicative of whether it had been selected for surveillance using Pegasus.

What is HLR lookup data?

The term HLR, or home location register, refers to a database that is essential to operating mobile phone networks. Such registers keep records on the networks of phone users and their general locations, along with other identifying information that is used routinely in routing calls and texts. Telecoms and surveillance experts say HLR data can sometimes be used in the early phase of a surveillance attempt, when identifying whether it is possible to connect to a phone. The consortium understands NSO clients have the capability through an interface on the Pegasus system to conduct HLR lookup inquiries. It is unclear whether Pegasus operators are required to conduct HRL lookup inquiries via its interface to use its software; an NSO source stressed its clients may have different reasons – unrelated to Pegasus – for conducting HLR lookups via an NSO system.

It needed to do so, it argued, to track down drug dealers using foreign sim cards to evade surveillance.

Insiders at the company were hesitant, a person familiar with the matter said. It was a risky proposition given the track record of customers such as the UAE. In 2016, it had tried to use NSO spyware to hack the phone of one of the most outspoken and respected Emirati human rights activists, Ahmed Mansoor. He was imprisoned by Emirati authorities one year later and is still in jail.

But the Guardian has been told an NSO committee reviewing the deal agreed to Dubai’s request. Potentially, it meant that authorities in Dubai would be able to bypass privacy and anti-hacking laws that would usually protect individuals living in democracies from being spied on without a warrant and having their phones hacked by a foreign government.

Some of the people in whom authorities showed a possible interest, leaked records now indicate, were not drug dealers at all. They were human rights activists and dissidents living in exile.

Using NSO’s signature software, Pegasus, Dubai’s rulers could seek to infiltrate any mobile phone they wanted in the UK, eavesdrop on calls, look at photos, read text messages and even turn a phone’s microphone or camera on remotely. In most cases, they could do it without leaving a digital fingerprint.

This is the power of NSO’s spyware – and why countries from Mexico to Saudi Arabia, Rwanda and India appear to have been willing to pay a high price for its capabilities.

This week, the Pegasus project, a media collaboration that included the Guardian and was coordinated by the French media group Forbidden Stories, revealed new allegations of abuse, with leaked records showing the phone numbers of journalists, dissidents and political activists.

Q&AWhat is the Pegasus project?

Show

The Pegasus project is a collaborative journalistic investigation into the NSO Group and its clients. The company sells surveillance technology to governments worldwide. Its flagship product is Pegasus, spying software – or spyware – that targets iPhones and Android devices. Once a phone is infected, a Pegasus operator can secretly extract chats, photos, emails and location data, or activate microphones and cameras without a user knowing.

Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based nonprofit journalism organisation, and Amnesty International had access to a leak of more than 50,000 phone numbers selected as targets by clients of NSO since 2016. Access to the data was then shared with the Guardian and 16 other news organisations, including the Washington Post, Le Monde, Die Zeit and Süddeutsche Zeitung. More than 80 journalists have worked collaboratively over several months on the investigation, which was coordinated by Forbidden Stories.

The database, which was the heart of the Pegasus project investigation, included the phone details of 13 heads of state, as well as diplomats, military chiefs and senior politicians from 34 countries.

Others whose numbers appear on the leaked list include the French president, most of his cabinet, reporters in Hungary and Mexico, 400 people in the UK, including a member of the House of Lords, two princesses – and a horse trainer.

Forensic analysis of a small sample from the database has shown some phones on the list were infected.

But the presence of a phone number in the data does not reveal whether a device was infected with Pegasus or subject to an attempted hack.

NSO has denied the database of numbers has anything to do with it or its customers. It says it has no visibility into its clients’ activities, and said the reporting consortium had made “incorrect assumptions” about which clients used the company’s technology.

NSO said the fact that a number appeared on the leaked list was in no way indicative of whether a number was targeted for surveillance using Pegasus. NSO also says the database has “no relevance” to the company.

It said it may be part of a larger list of numbers that might have been used by NSO Group customers “for other purposes”.

No country has admitted being a customer of NSO’s technology.

Under surveillance: the company and its clients

From humble beginnings in 2010, NSO has become in effect a company that helps its clients spy on the world. This week, the Pegasus projecthas raised new concerns about the scale and depth of the surveillance campaigns pursued by the company’s government clients – and more generally the lack of regulations around the many firms that now sell military-grade spyware.

Based in Herzliya, NSO Group has come a long way in a short period. The name is derived from the initials of the men who launched it: the friends Niv Carmi, Shalev Hulio and Omri Lavie.

Hulio, who served in the Israel Defence Forces (IDF), has said the idea for the company came after he and Lavie received a phone call from a European intelligence service, which had learned the pair had the know-how to access people’s phones.

“Why aren’t you using this to collect intelligence?” the agency is said to have asked.

The proliferation of smartphones and encrypted communications technology, from Signal to WhatsApp and Telegram, meant intelligence and law enforcement agencies had gone “dark”, unable to monitor the activities of terrorists, paedophiles and other criminals.

“They said we didn’t really understand, that the situation was grave,” Hulio recalled. So grave, in fact, that when NSO began selling its technology, it quickly expanded, and currently employs about 750 staff.

The company is the world leader in a niche market: providing states with “off the shelf” cyber capabilities that allow them to compete with the National Security Agency (NSA) in the US and the UK’s GCHQ.

From the start, NSO cultivated an image as a cutting-edge crime fighter whose surveillance tools were used to stop terrorists. “This is really for the Bin Ladens of the world,” Tami Mazel Shachar, then a co-president of NSO Group, told 60 Minutes in 2019.

The firm has also said it is the antithesis of a mass surveillance company, with clients allegedly handling fewer than 100 targets at any given time. A source familiar with the matter said the average number of annual targets per customer was 112.

Incidents of abuse, the company has suggested, are rare and investigated by compliance officials. When allegations of abuse have emerged, the company has said it cannot disclose the identities of its government clients. A person familiar with NSO operations who spoke on the condition of anonymity said that in the last year alone, it had terminated contracts with Saudi Arabia and Dubai in the United Arab Emirates over human rights concerns.

‘Digital spy in your pocket’

The Pegasus project has raised new questions about this narrative. It has also highlighted the Israeli government’s close links to the company.

“The [company’s] regulations are a state secret,” said one insider. But the group is ultimately guided by one golden rule: “There are three jurisdictions you don’t fuck with: the US, Israel and the Russians.”

Its first client, in 2011, was Mexico, a country that remains a major importer of spyware.

Over an 18-month period in 2016-17 the numbers of more than 15,000 people in Mexico appeared on the leaked database. They included the phone numbers of dozens of journalists, editors and at least 50 people close to the country’s current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador .

This doesn’t mean they were subject to an attempted hack using Pegasus or were infected with it. It does suggest some government clients of NSO Group had a pool of Mexican people they were interested in.

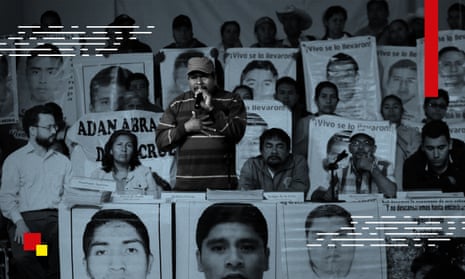

Mexico has been accused before. In 2020, media reports began to emerge documenting serious abuses of NSO’s technology, including the targeting of international experts who were examining the case of 43 students who disappeared after they were abducted by police.

Around the same time, halfway across the world, another client of NSO was sending Mansoor suspicious text messages on his iPhone. When he sent the links to researchers at Citizen Lab, which is affiliated with the University of Toronto, it found the link was infected with malware made by the Israeli company. Clicking it would have turned Mansoor’s phone into a “digital spy in his pocket”, tracking his movements and listening to his calls.

Within a year of the discovery, security forces raided Mansoor’s home and arrested him. A report by Human Rights Watch found Mansoor – a father of four who has been described as a poet and an engineer – spent years in an isolation cell following his arrest. His “crimes” included WhatsApp exchanges with human rights organisations.

In October 2018, NSO faced a barrage of criticism after Citizen Lab announced it had discovered that a device belonging to another dissident, a Saudi named Omar Abdulaziz who was living in exile in Canada, had been infected by malware.

It was only a few days later, following the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, that the significance of Abdulaziz’s targeting would become evident.

Khashoggi and Abdulaziz had been in touch with each other. In interviews and in a court filing, Abdulaziz said he believed the targeting had been a “crucial factor” in the killing of the Washington Post journalist and the harassment and imprisonment of his own family in the kingdom.

One former official told the Guardian the US uncovered signs that surveillance was a factor in the killing. “We did notice they [Saudi Arabia] had focused on him. We didn’t know that until after the murder, but we did find intercepts of people talking about surveilling journalists. I don’t know if that was NSO,” said Kirsten Fontenrose, a senior official at the US National Security Council covering Saudi Arabia at the time.

Khashoggi’s fiancee, Hatice Cengiz, was hacked using Pegasus by an NSO client – believed to be Saudi Arabia – four days after the journalist was killed, according to an examination of her phone by Amnesty International’s security lab. Other friends and associates of the journalist were also hacked or targeted by the company’s clients. Within months of the murder, Saudi Arabia was cut off from NSO, though its access would be reinstated within six months.

In a statement, NSO said: “Our technology was not associated in any way with the heinous murder of Jamal Khashoggi. We can confirm that our technology was not used to listen, monitor, track, or collect information regarding him or his family members mentioned in your inquiry.”

New owners, new concerns

In 2019, the US-based private equity fund Francisco Partners decided to sell NSO Group to a new group of investors. The deal was led by a London-based firm called Novalpina Capital, whose fund bought a majority stake of the company along with the founders of NSO in an acquisition valued at about $1bn.

At Novalpina Capital, debate ensued internally about how the private equity firm should approach its new investment, according to a person familiar with the matter. NSO was not a household name, but despite its claims that its spyware was saving lives by preventing terrorist attacks, human rights organisations were asking searching questions of the group.

In April, Amnesty International, among others, signed a letter addressed to Novalpina demanding accountability for the targeting of “a wide swath of civil society”, including two dozen human rights defenders in Mexico, one of its own employees, Abdulaziz, Mansoor, Ghanem Almasarir, a London-based Saudi satirist, and Yahya Assiri, another Saudi activist.

Amnesty said: “These individuals and organisations appear to have been targeted solely as a result of their criticism of governments that utilised the spyware or because of their work bearing on human rights issues of political sensitivity to those governments. Thus, this targeting is in violation of internationally recognised human rights.”

Stephen Peel, a British financier and co-founder of Novalpina, led an effort by the private equity firm to engage with the human rights groups and researchers who had been sounding alarms about its practices for years. In a lengthy exchange of letters with Amnesty signed by Novalpina, Peel promised to tackle their concerns.

Within months of making that pledge, two sources familiar with the matter said, Dubai was allowed to expand its use of the spyware into the UK. In September 2019, the company also unveiled a new human rights policy and adopted “guiding principles” to protect vulnerable populations, including journalists and activists. In the meantime, allegations of abuse by NSO clients kept streaming in.

WhatsApp takes action

Then, another technology giant entered the fray.

In October 2019, WhatsApp revealed that 1,400 of its users had been targeted with Pegasus through a vulnerability in its app. Individuals who were affected by the attack, and were alerted by WhatsApp, included members of the clergy in Togo and dozens of journalists in India, Rwanda and Morocco.

“The really big tectonic shift in our understanding of NSO’s capabilities happened around the WhatsApp attack when we just saw obviously a raft of zero-click attacks. And that’s just like another order of magnitude of sophistication,” said John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at Citizen Lab.

In a continuing legal battle over the case, NSO argued before a US court that it ought to be granted immunity in the case because the company’s software had been used on behalf of foreign government clients without its knowledge or approval.

Being a client of NSO, said one person who previously served as a broker in the industry, was a bit like gun ownership in the US.

“You are supposed to use a gun to protect yourself, but who is to stop you from robbing a bank?” they said. “You ask me whether it was known by NSO that Pegasus would be used to go after journalists, human rights activists, I would tell you of course they knew. That is my opinion. Of course everyone understands that. But has it been said? Did they say ‘we will use it for regime opponents’? No, they did not say that.”

The Guardian put a series of questions to NSO and Novalpina about its dealings with the UAE. They declined to comment.

Show your support for the Guardian’s fearless investigative journalism today so we can keep chasing the truth